English

“If they had told me what I have to say, in order to meet with their approval, I’d be bound to say it, sooner or later.” […]

“Perhaps I’ve said the thing that had to be said, that gives me the right to be done with speech […], without knowing it.” […]

“perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story”

(The Unnamable, SW II 329, 387, 407)

“But finally I asked if I knew exactly what the man – I would like to give his name but cannot – what exactly was required of the man, what it was that he would not or could not say. No, was the answer, after some little hesitation, no, I did not know what the poor man was required to say, in order to be pardoned, but would have recognized it at once, yes, at a glance, if I had seen it.”

(As the Story Was Told, SW IV 424)

“BAM: You gave him the works?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: And he didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: He wept?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Screamed?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Begged for mercy?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: But didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: The why stop?

BOM: He passed out.”

(What Where, SW III, 496)

It is not clear when Samuel Beckett first encountered Franz Kafka's work – perhaps, as Van Hulle and Nixon speculate, as early as around 1930 in English translation (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 101). By the 1950s at the latest, however, there is clear evidence of Beckett’s reading of Kafka, not only in his work, but also in letters and interviews – in which he signalled that he had not read Kafka extensively, partly because of a certain ‘anxiety of influence’, a feeling that this writer was too close to him: “Je m'y suis senti chez moi, trop, c'est peut-être cela qui m'a empêché de continuer.” (1954; Letters II 462) As he said in an interview with Israel Shenker in the New York Times in 1956, he had until then only read Das Schloss in German and some other pieces in French and English (there is also evidence that he had read Der Prozess). In this interview, however, he also diagnosed a clear difference between himself and Kafka: "The Kafka hero has a coherence of purpose. He's lost but he's not spiritually precarious, he's not falling to bits. My people seem to be falling to bits. Another difference. You notice how Kafka's form is classic, it goes on like a steamroller – almost serene. It seems to be threatened the whole time – but the consternation is in the form. In my work there is consternation behind the form, not in the form." He repeatedly stated this perception: “Sam also said Kafka's subject-matter called for a more disjointed style.“ (Atik 2001, 66); “What struck me as strange in Kafka was that the form is not shaken by the experience it conveys” (1962, letter to Ruby Cohn, quoted in Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 101). However, this conflict between similarity and contrast already reveals Beckett’s intense engagement with Kafka’s work, which continued into his later years: In 1982, Beckett read a biography of Kafka as well as the latter’s diaries (Letters IV 588-592, 604; “that luckless great man”, Letters IV, 590), and even in the last year of his life, Kafka was among the few books in his room (Knowlson 1996, 701).

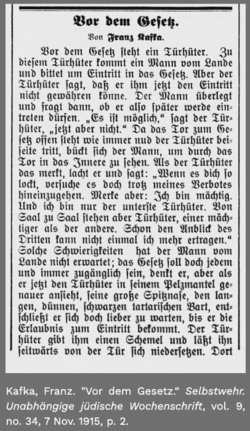

One text by Kafka in particular is repeatedly and clearly reflected in Beckett's work and, like Walther von der Vogelweide, assumes a structural poetological function: the famous parable of the doorkeeper, part of the great novel Der Prozess (Chapter 9) and first published separately as "Vor dem Gesetz" in 1915. Kafka's story of the "countryman" who spends his life trying to enter the law, asking countless questions about it and yet failing to find the right solution until his death, becomes a central motif for Beckett from the 1950s onwards at the latest – Beckett’s characters are constantly searching for the one solution, the one word that will redeem them from their fate, meet the external demands, and open the door to their story: “If they had told me what I have to say, in order to meet with their approval, I’d be bound to say it, sooner or later.” […] “Perhaps I’ve said the thing that had to be said, that gives me the right to be done with speech […], without knowing it.” […] “perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story” (The Unnamable, SW II 329, 387, 407).

The significance of this topos is continually expanded throughout Beckett's post-war work: In “As the Story Was Told,” published in 1973 by Suhrkamp as a commissioned contribution to a memorial volume for Günter Eich, Beckett, influenced by his experiences in the French Resistance, connects it with the topic of torture (whether this is also a statement directed at Eich is an open research question: Beckett met Günter Eich in March 1961 (Wilm/Nixon 2013, 28), but, according to his own statement, hardly knew him and initially did not really know what he should contribute to the memorial volume; Letters IV 340-341): A voice reports on torture sessions that were held in a nearby tent (“As the story was told me I never went near the place during sessions. […] I asked what sessions and these in in their turn were described, their object, duration, frequency and harrowing nature.” SW IV 423). The voice itself recognizes that its role was to wait for a specific statement from the tortured person – the statements are continuously transmitted to it in writing: “as I watched a hand appeared in the doorway and held out to me a sheet of writing. I took and read it, then tore it in four and put the pieces in the waiting hand to take away.” (SW IV 424) But even the person who appears to be the ruler and the one who commissioned the attack cannot say what the redeeming word would have been that would have spared the man his torment: “But finally I asked if I knew exactly what the man – I would like to give his name but cannot – what exactly was required of the man, what it was that he would not or could not say. No, was the answer, after some little hesitation, no, I did not know what the poor man was required to say, in order to be pardoned, but would have recognized it at once, yes, at a glance, if I had seen it.” (SW IV 424) Beckett takes up this expanded topos again in his last play What Where, in which the creatures interrogate each other under torture in order to extract the one word:

“BAM: You gave him the works?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: And he didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: He wept?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Screamed?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Begged for mercy?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: But didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: The why stop?

BOM: He passed out.”

(What Where, SW III, 496)

The significance of torture in Beckett’s work is another open research question – connections can certainly be drawn here to Kafka’s In der Strafkolonie, one of the most shocking depictions of this topic in the 20th century, which is connected to Beckett via the topos of writing as carving into skin (compare How It Is: “with the nail of the right index I carve […] from left to right and top to bottom as in our civilisation I carve my Roman capitals” […], “nail on skin”; SW II 460, 474). A further level of meaning of this topos can be seen in Texts for Nothing 5: “This evening, the session is calm, there are long silences when all fix their eyes on me, that’s to make me fly off my hinges, I feel on the brisk of shrieks, it’s noted. Out of the corner of my eye I observe the writing hand, all dimmed and blurred by the – by the reverse of farness.” (SW IV 310) The "sessions“ here are also writing sessions, the author is the torturer, the creature the victim – in a figurative sense, it ultimately refers to the author's agonizing search for the one word that concludes his text, that allows him and his characters to end (and only the author will eventually know when it will have been the right word). Beckett thus uses the topos again to inscribe the author as a character into the work. In his last prose text, Beckett expands the scope of meaning once again: the aging author is again searching for the one word, “a word he could not catch” – “that missing word” (Stirrings Still, SW IV 492), accompanied by "strokes and cries“ (489), which initially denote human sounds and bells ringing through the open window, but also reintroduce the motif of torture – the author is thus tortured by the striking of the clock, by the passing of time, and continues to search for the redeeming word that will allow him to end: "Time and grief and self so-called. Oh all to end.“ (492). Beckett's last published text, the poem "What Is the Word", takes up this theme again and adds a further, theological level of meaning – the inherent human longing and futile task remains to ask what the divine word is ("In the beginning was the Word"):

„folly for to need to seem to glimpse afaint afar away over there what –

what –

what is the word –

what is the word”

(SW IV 51)

The fact that Beckett takes up the topos of the agonising search for the one redeeming word in his last prose work (Stirrings Still), his last play (What Where) and in his last poem (“What Is the Word”) impressively demonstrates its centrality – and the importance of Kafka for his work.

Further reading/sources: Van Hulle/Nixon 2013; Knowlson 1996; Ricks 1987.

Deutsch

“If they had told me what I have to say, in order to meet with their approval, I’d be bound to say it, sooner or later.” […]

“If they had told me what I have to say, in order to meet with their approval, I’d be bound to say it, sooner or later.” […]

“Perhaps I’ve said the thing that had to be said, that gives me the right to be done with speech […], without knowing it.” […]

“perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story”

(The Unnamable, SW II 329, 387, 407)

“But finally I asked if I knew exactly what the man – I would like to give his name but cannot – what exactly was required of the man, what it was that he would not or could not say. No, was the answer, after some little hesitation, no, I did not know what the poor man was required to say, in order to be pardoned, but would have recognized it at once, yes, at a glance, if I had seen it.”

(As the Story Was Told, SW IV 424)

“BAM: You gave him the works?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: And he didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: He wept?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Screamed?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Begged for mercy?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: But didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: The why stop?

BOM: He passed out.”

(What Where, SW III, 496)

Wann Samuel Beckett dem Werk Franz Kafkas zum ersten Mal begegnet ist, lässt sich nicht eindeutig nachvollziehen – vielleicht, wie Van Hulle und Nixon spekulieren, bereits um 1930 in englischer Übersetzung (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 101). Spätestens in den 1950ern finden sich jedoch eindeutige Lesebelege, nicht nur im Werk, sondern auch in Briefen und Interviews – in denen er signalisierte, Kafka nicht umfänglich rezipiert zu haben, auch wegen einer gewissen ‚anxiety of influence‘, einer Empfindung, dass ihm dieser Schriftsteller zu nahe sei: “Je m’y suis senti chez moi, trop, c’est peut-etre cela qui m’a empeché de continuer.” (1954; Letters II 462) Er habe nur Das Schloss auf Deutsch gelesen sowie einiges andere in Französisch und Englisch, wie er 1956 in einem Interview mit Israel Shenker in der New York Times sagte (auch für Der Prozess ist die Lektüre belegt). In diesem Interview diagnostizierte er jedoch auch einen deutlichen Unterschied zwischen sich und Kafka: "The Kafka hero has a coherence of purpose. He's lost but he's not spiritually precarious, he's not falling to bits. My people seem to be falling to bits. Another difference. You notice how Kafka's form is classic, it goes on like a steamroller - almost serene. It seems to be threatened the whole time - but the consternation is in the form. In my work there is consternation behind the form, not in the form." Diese Wahrnehmung bekräftigte er mehrfach in anderen Aussagen: “Sam also said Kafka's subject-matter called for a more disjointed style.“ (Atik 2001, 66); “What struck me as strange in Kafka was that the form is not shaken by the experience it conveys” (1962, Brief an Ruby Cohn, zitiert in Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 101). In diesem Zwiespalt zwischen Ähnlichkeit und Abhebung zeigt sich jedoch bereits die intensive Auseinandersetzung Becketts mit Kafkas Werk, die sich bis in die späten Jahre fortsetzte: Im Jahre 1982 las Beckett eine Biographie Kafkas und dessen Tagebücher (Letters IV 588-592, 604; “that luckless great man”, Letters IV, 590), und noch in seinem letzten Lebensjahr fand sich Kafka unter den wenigen Büchern in seinem Zimmer (Knowlson 1996, 701).

In Becketts Werk schlägt sich vor allem ein Text Kafkas wiederholt in aller Deutlichkeit nieder und nimmt wiederum, wie bei Walther von der Vogelweide, eine literaturtheoretisch-poetologische Funktion ein: die berühmte Türhüter-Parabel, Teil des großen Romans Der Prozess (9. Kapitel) und zunächst 1915 einzeln als „Vor dem Gesetz“ veröffentlicht. Kafkas Geschichte vom „Mann vom Lande“, der ein Leben lang versucht, in das Gesetz einzutreten, hierzu unzählige Fragen stellt und dennoch die richtige Lösung bis zu seinem Tod nicht findet, wird für Beckett spätestens ab den 1950ern zu einem zentralen Motiv – seine Figuren suchen permanent nach der einen Lösung, dem einen Wort, das sie von ihrem Schicksal erlöst, den geforderten Ansprüchen gerecht wird und die Tür zu ihrer Geschichte öffnet: “If they had told me what I have to say, in order to meet with their approval, I’d be bound to say it, sooner or later.” […] “Perhaps I’ve said the thing that had to be said, that gives me the right to be done with speech […], without knowing it.” […] “perhaps they have carried me to the threshold of my story, before the door that opens on my story” (The Unnamable, SW II 329, 387, 407). Die Bedeutung dieses Topos wird durch Becketts Nachkriegswerk hindurch immer weiter ausgeweitet: In “As the Story Was Told”, 1973 als bestellter Beitrag zum einem Gedächtnisband für Günter Eich bei Suhrkamp veröffentlicht, verbindet Beckett, geprägt durch seine Erfahrungen in der französischen Résistance, den Topos mit dem Thema Folter (ob Beckett hiermit auch eine Aussage in Richtung Eich verbindet, ist eine offene Forschungsfrage: Beckett lernte Günter Eich im März 1961 kennen (Wilm/Nixon 2013, 28), kannt ihn jedoch nach eigener Aussage kaum und wusste zunächst nicht wirklich, was er zum Gedächtnisband beitragen soll; Letters IV 340-341): Eine Stimme berichtet von Foltersitzungen („sessions“), die in einem nahegelegenen Zelt abgehalten wurden (“As the story was told me I never went near the place during sessions. […] I asked what sessions and these in in their turn were described, their object, duration, frequency and harrowing nature.” SW IV 423) Die Stimme selbst erkennt, dass sie die Rolle innehatte, auf eine bestimmte Aussage des Gefolterten zu warten – die Aussagen werden ihr laufend schriftlich übermittelt: “as I watched a hand appeared in the doorway and held out to me a sheet of writing. I took and read it, then tore it in four and put the pieces in the waiting hand to take away.” (SW IV 424) Doch auch der scheinbar also als Machthaber und Auftraggeber Fungierende kann nicht sagen, welches nun eigentlich das erlösende Wort gewesen wäre, das dem Mann seine Qualen erspart hätte: “But finally I asked if I knew exactly what the man – I would like to give his name but cannot – what exactly was required of the man, what it was that he would not or could not say. No, was the answer, after some little hesitation, no, I did not know what the poor man was required to say, in order to be pardoned, but would have recognized it at once, yes, at a glance, if I had seen it.” (SW IV 424) Diesen erweiterten Topos nimmt Beckett in seinem letzten Theaterstück What Where wieder auf, bei dem sich die ‚Kreaturen‘ gegenseitig unter Folter verhören, um das eine Wort herauszupressen:

“BAM: You gave him the works?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: And he didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: He wept?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Screamed?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: Begged for mercy?

BOM: Yes.

BAM: But didn’t say it?

BOM: No.

BAM: The why stop?

BOM: He passed out.”

(What Where, SW III, 496)

Die Bedeutung der Folter in Becketts Werk ist eine weitere offene Forschungsfrage – sicherlich lassen sich hier auch Verbindungen zu Kafkas In der Strafkolonie ziehen, einer der krassesten Darstellungen dieses Themas im 20. Jahrhundert, die mit Beckett über den Topos des Schreibens als Einritzen in der Haut verbunden (vgl. How It Is: “with the nail of the right index I carve […] from left to right and top to bottom as in our civilisation I carve my Roman capitals” […], “nail on skin”; SW II 460, 474). Ein weiterer Bedeutungslevel des Gesamttopos zeigt sich jedoch in Texts for Nothing 5: “This evening, the session is calm, there are long silences when all fix their eyes on me, that’s to make me fly off my hinges, I feel on the brisk of shrieks, it’s noted. Out of the corner of my eye I observe the writing hand, all dimmed and blurred by the – by the reverse of farness.” Die Sitzungen („sessions“) sind hier also gleichzeitig Schreibsitzungen, der Autor ist der Folternde, die Figur das Opfer – in übertragenem Sinne ist letztlich die quälende Suche des Autors nach dem einen Wort gemeint, das seinen Text abschließt, das ihm und seinen Figuren ermöglicht zu enden – und nur der Autor wird wissen, wann es das richtige Wort gewesen ist. Beckett verwendet also den Topos wiederum dazu, den Autor als Figur mit ins Werk hineinzuschreiben. In seinem letzten Prosatext erweitert Beckett den Bedeutungsumfang noch einmal: Der alternde Autor ist wiederum auf der Suche nach dem Wort “and here a word he could not catch” – “that missing word” (Stirrings Still, SW IV 492), begleitet von „strokes and cries“ (489), die zwar zunächst durch das offene Fenster dringende menschliche Laute und Glockenschläge bezeichnen, aber ebenso das Motiv der Folter wieder einbringen – der Autor wird so durch die Schläge der Uhr, durch die vergehende Zeit gefoltert und bleibt weiterhin aus der Suche nach dem erlösenden Wort, das ihm das Enden ermöglicht: „Time and grief and self so-called. Oh all to end.“ (492). Becketts letzter veröffentlichter Text, das Gedicht „What Is the Word“ nimmt diesen Topos wiederum auf und fügt einen weiteren, theologischen hinzu – die dem Menschen ureigene vergebliche Sehnsucht und Aufgabe bleibt es zu fragen, was das göttliche Wort ist („Im Anfang war das Wort“):

„folly for to need to seem to glimpse afaint afar away over there what –

what –

what is the word –

what is the word”

(SW IV 51)

Dass Beckett den Topos der quälenden Suche nach dem einen erlösenden Wort in seinem letzten Prosawerk (Stirrings Still), seinem letzten Theaterstück (What Where) und in seinem letzten Gedicht („What Is the Word“) aufnimmt, belegt eindrucksvoll dessen Zentralität – und die Bedeutung Kafkas für sein Werk.

Weiterführende Literatur/Quellen: Van Hulle/Nixon 2013; Knowlson 1996; Ricks 1987.