English

Since the 1960s, Beckett has used music to a greater extent as another language, closely intertwined with language and literature – “As though they had linked their arms” (Cascando, SW III 346) –, for example in the radio pieces Words and Music and Cascando as well as in the television pieces Nacht und Träume and Ghost Trio. Here, music and words appear as constant voices within the fictional author and his creatures – while in How It Is or Not I, for example, this is an unstoppable voice constantly speaking the text, in Cascando and Ghost Trio the music appears as a permanent ‘stream of consciousness’ that is only occasionally interrupted. Like memory (“that old past ever new, [...] with all its hidden treasures of promise for tomorrow, and of consolation for today.” Texts for Nothing 10, SW IV 328) and the invented stories („devising it all for company“, Company, SW IV 443), music serves as a consolation for the fictional author (“My comforts! Be friends!” Cascando, SW III 334), as a bridge on the escape of the longing prisoner into memory (of beloved person), dream and imagination (Words and Music, Ghost Trio).

Of central importance here are two German-speaking composers – Franz Schubert and Ludwig van Beethoven. Almost all biographical witnesses report on Beckett's passion for Schubert: Beckett experienced Schubert's music not only in concerts (e.g., the song cycle Winterreise with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in Paris; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218) and on records (in 1975, Beckett describes his listening experience of the Winterreise as “shivering through the grim journey again”; Knowlson 1996, 626), but played Schubert‘s Impromptus and Sonatas himself on the piano (Knowlson 1996, 655) and also sang Schubert’ songs himself (Lawley 2001, 263; Atik 2001); on Beckett’s annotations in a Schubert biography see Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 216-218.

Schubert’s melancholic songs in particular were Beckett’s constant companions from an early age: „Beckett’s attraction to the musical form of the Lied is well known, as is his admiration of the composer Franz Schubert. In the confluence of text and music, mood and tone, Beckett found an expression of suffering and of Schwermut with which he could identify.” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 216) Accordingly, Schubert appears again and again in Beckett’s work, from the early More Pricks Than Kicks (compare Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218) via All That Fall (1956; see above) to his last works, Nacht und Träume und What Where („It is winter. Without journey.“ SW III 500; compare Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218). In addition to Winterreise, Der Tod und das Mädchen appears again and again, for example in All That Fall, where the string quartet sounds ominously twice from a house by the wayside (SW III 155, 184).

For Beckett, the quartet is closely linked to the corresponding text by Matthias Claudius: „Beckett’s mediation of German poetry via their setting in song (Lieder) is evident from his copy of Walter and Paula Rehberg’s Franz Schubert, sein Leben und Werk (1947 [1946]). In the index of poems set to music by Schubert, Beckett put a pen line beside Claudius’ name. Furthermore, he proceeded to write out the title and first line of various poems set to music by Schubert […]. At the top of this list, Beckett noted four poems by Claudius: ‘Abendlied’, ‘An die Nachtigall’, ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’ and ‘Wiegenlied’.” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 86; compare 217) The text of Claudius, whose poems Beckett memorized (Wilm/Nixon 2013, 22; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 86; Atik 2001, 65), is also an inspiration in Krapp’s Last Tape: „When the protagonist in Krapp’s Last Tape is said to ‘look over his shoulder into the darkness backstage left’, he senses the presence of death, which in Beckett’s production notes is called ‘Hain’ (220). Beckett explained to James Knowlson that he alluded to Matthias Claudius’ poem ‘Death and the Maiden’ (set to music by Franz Schubert) and to the eighteenth-century German poet’s use of the word ‘Hain’ to refer to the death figure. In Beckett’s personal library, his copy of Matthias Claudius’ Sämmtliche Werke contains a card, inserted between pages 884 and 885, quoting a letter from Claudius to Voss (21 August 1774) that includes ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’ […]. But the image of Hain he had in his mind is most probably the unmarked illustration next to the title page” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 10). As James Knowlson reports: „He was almost obsessed by Matthias Claudius’ poem ‘Death and the Maiden’ in which Death is seen as a comforter, welcoming the maiden into its arms.” (Knowlson 1996, 626)

However, the most comprehensive reference to Schubert in Beckett’s work is the television play Nacht und Träume (SW III 487-490), which uses the last seven bars of Schubert's song „Nacht und Träume“ (the text is a poem by Matthäus von Collin) with the line "Holde Träume kehret wieder" (“Lovely dreams, return!”) at a central point: Here, music (first hummed, then sung) serves the nightly figure (the „Dreamer“, again characterised as an imagining author-figure, „bowed head resting on hands“, 489) as a bridge into dreams and imagination – here the longing dream of a consolation from beyond (which, through the repetition in „close-up“ (490) of the „dreamt self“ (488) is handed over to the viewer). The central function of music as a symbol of the escape of those trapped in the barren reality into memory, dreams and imagination is clearly recognizable here.

Of equal importance to Beckett is the music of Ludwig van Beethoven: Early in his childhood and studies, as well as later in life, Beckett played Beethoven's piano variations himself (Knowlson 1996, 7-8, 95, 655). In addition to Romain Rolland's Beethoven biography, Beckett also had another Beethoven biography and the volume Beethoven im Gespräch in his library (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215). Accordingly, Beethoven is „present throughout Beckett’s work” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 214). Beckett’s early work is full of references to Beethoven, for instance to the “unsterbliche Geliebte” in Dream of Fair to Middling Women (Beckett 1992, 138; vgl. RR 33) or to Beethoven’s last quartet (Op. 135 in F major, „Der schwergefasste Entschluss“), with the line „Muss es sein? Es muss sein! Es muss sein!“ appearing in Beckett‘s poem Malacoda („must it be it must be it must be“, SW IV 29; compare Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215; Ackerley/Gontarski 2006, 45; Beckett took this up again in an early version of Play, c. 1962, see Knowlson 1996, 498); on further references to Beethoven in Beckett’s early work see Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215; Ackerley/Gontarski 2006, 45.

Beckett’s Beethoven-inspired poetological discussion in the famous letter to Axel Kaun (1937) – „Steckt etwas lähmend Heiliges in der Unnatur des Wortes, was zu den Elementen der anderen Künste nicht gehört? Gibt es irgendeinen Grund, warum jene fürchterlich willkürliche Materialität der Wortfläche nicht aufgelöst werden sollte, wie z.B. die von großen schwarzen Pausen gefressene Tonfläche in der siebten Symphonie von Beethoven, so dass wir sie ganze Seiten durch nicht anders wahrnehmen können als etwa einen schwindelnden unergründliche Schlünde von Stillschweigen verknüpfenden Pfad von Lauten?“ (Disjecta 52-53) can also be found almost literally in Dream of Fair and Middling Women (Beckett 1992, 138) (compare Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 214-216). What has not been noticed so far is that Beckett also oriented himself towards Beethoven in his middle creative phase, with a long memory for Romain Rolland's short but impressive biography: For example, Krapp in Krapp’s Last Tape, plagued by digestive problems, short-sighted and hard of hearing („Very near-sighted (but unspectacled). Hard of hearing.”, SW III 217) is in all these details a mirror image of the Beethoven described by Romain Rolland. And not only in those: Like Krapp („until that memorable night […] in the howling wind, never to be forgotten, when suddenly I saw the whole thing. The vision at last. […] the fire that set it alight. What I suddenly saw then was this, that the belief I had been going on all my life, namely –“, SW III 222) Rolland's Beethoven also tends to enthusiastic outbursts: „Ich schreibe jetzt eine Oper! Ich habe die Hauptgestalt in mir, wo ich gehe und stehe. Nie war ich noch auf solcher Höhe! Alles Licht – alles rein und klar!“ (RR 31); Rolland‘s description of Beethoven – “unaufhörlich war er sterblich verliebt, unaufhörlich träumte er von unerhörtem Glück, das zerrann und bittere Leiden im Gefolge hatte. In diesem Wechsel von Liebe und stolzem Sich-dagegen-Auflehnen ist die reichste Quelle von Beethovens Inspiration zu suchen, bis dann später das Feuer seines Temperamentes nur noch unter melancholischer Resignation glimmt.“ (RR 25) – accordingly can be read in parallel with Krapp: “the fire that set it alight” (SW III 222), “with the light of the understanding and the fire” (222), and finally in the play’s decisive expression “Not with the fire in me now” (226).

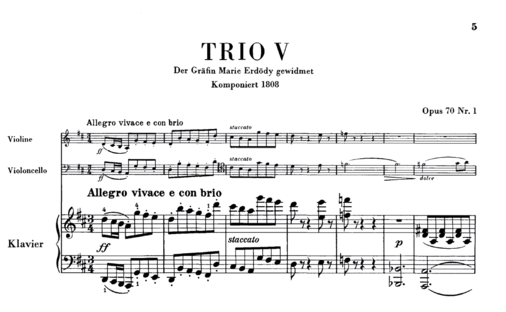

The most detailed and precise use of music in Beckett's entire oeuvre, however, can be found in the television play Ghost Trio, which is based on Beethoven's so-called "Geistertrio" (Op. 70 No. 1) (the Beethoven trio's connection to ghosts only arose posthumously through its temporal association with Beethoven's plans for an opera based on Macbeth – Beckett was aware of this connection, cf. Knowlson 1996, 621). Beckett's meticulous work on Beethoven's music during the creation of Ghost Trio (Knowlson 1996, 621-622) is reflected in the nuanced use of various musical passages in the play. As in ...but the clouds... and Ohio Impromptu, the longing for a lost/deceased lover is a central theme of the play. As in Nacht und Träume, in Ghost Trio music represents the search for solace in longing, dreams, imagination, and memory – which is all that is left to a creature imprisoned in its fate; the music appears as a continuous inner voice of memories and dreams of the beloved (the idea of the deaf Beethoven, who only hears the music internally, fits in with this).

In Ghost Trio, however, the Beckettian themes of longing, dream, imagination, and memory undergo a further modification or intensification: The creature in the play is not only trapped in a barren space typical of Beckett, but also in this memory, this longing – the barrenness of the space reflects that there is nothing left for the character except this yearning memory. The play depicts a gradual process of becoming aware of this imprisonment and of liberation from this yearning memory through self-knowledge. In order to understand this drama within the play, another background to the play, also from German culture, is helpful: Beckett received Heinrich von Kleist's essay Über das Marionettentheater (1810) as a gift from a German actress in 1969 and subsequently referred to this text several times in his directing, including in the BBC adaptation of Ghost Trio (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 97; Knowlson 1996, 584, 632-633). Kleist's descriptions of the marionette, whose lack of self-awareness results in greater elegance and symmetry in its movements, and of the fencing bear, whose lack of self-awareness prevents him from falling for feints, make it even clearer that Ghost Trio is a drama of becoming aware: The puppet, held by the threads of memory, suddenly deviates from its eternal repetitions and realizes in three moments of self-awareness (close-up of the cassette recorder, close-up of the face in the mirror, appearance of the messenger boy) that the remembering-dreaming hope in which it is trapped is in vain and that the longed-for woman will never return.

Let us re-examine the piece, which, like Beethoven’s trio, is divided into three parts – Pre-action, Action and Re-action: In the first part, the Pre-action, the commenting „Female Voice“ introduces the elements of the piece, the parts of the room and the figure. In part two, the Action, the character then goes through a cycle of behavior, each of which the voice comments on in the future tense („He will now …“); when the figure reaches the bed, however, to the commentator's surprise, it deviates from its previous, repetitive, automatic, puppet-like, unconscious behavior and instead looks in the mirror – and afterwards, instead of going to the door, as announced, goes to its seat. (The topos of imprisonment in repetition appears in many of Beckett’s works, in Waiting for Godot and Endgame as well as in Footfalls, Rockaby, Come and Go, Quad, What Where, Ping, Lessness etc. The creatures are here imprisoned in repetitions as much as in rooms.)

What actually happened here, however, is revealed in the uncommented repetition in Re-action (“Repeat.” is the final instruction of the voice; SW III 435): After the figure has opened the door for the first time in vain, through which he longs for the woman to come, there follows the first close-up of the cassette recorder from which the music is playing: „Cut to close-up from above of cassette on stool” (SW III 436). Here (in the BBC version, contrary to the printed version, 433) the cassette recorder can be seen as such for the first time – symbolizing the figure’s first step to self-awareness: It realizes that his longing is only for a canned memory (an analogue to the „recorded vagitus“ in Breath (SW III 397) and of course to Krapp’s recordings in Krapp’s Last Tape, which he calls „P.M.s“ (post mortems; SW III 220)), not a reality. Afterwards, the figure, instead of going to its bed (hence instead of falling into the monotonous rhythm of waking and sleeping; compare „no braving sleep“, Ohio Impromptu, SW III 471), goes to the mirror – “Cut to close-up of F’s face in the mirror” (SW III 437) –, where, we can interpret, it becomes aware of itself and its condition (old, alone) and sadly bows its head (“Head bows”, 437). On the second and final walk to the all-important door, the longing is finally disappointed – the messenger boy (who appears here as in Waiting for Godot, though here only once; Beckett himself pointed to the similarity to Godot, see Knowlson 1996, 621-622) shakes his head (“Boy shakes head faintly”, 437) and thus signalizes that the longed-for beloved finally will not come, is irretrievably gone. The figure returns one last time to the old dream, to the music, which then plays out – after which the figure looks clearly into the camera for the first time and hints at a smile. Through self-awareness, the puppet is finally freed from the prison of its memory (a similar ending can be found in the equally memory-centered That Time).

What role does music play here? Beckett here uses his detailed knowledge of Beethoven's composition as well as his keen awareness of the gestural potential of music (which he makes explicit for instance in the stage directions for ‘Music’ as an agent in Words and Music: „Warm suggestion“, „Renews timidly“ (SW III 334), „Discreet suggestion“ (335), „More confident suggestion“, „Invites“, „Brief rude retort“ (336)). Accordingly, Beckett uses the Beethoven themes in Ghost Trio very consciously – he breaks Beethoven's Largo (the middle piece of the trio) into suitable pieces and changes the original order for his own dramaturgy. All passages that Beckett uses for his piece begin with the main theme of the Largo on the violin. There are on the whole eight instances where the music is played: In the still entirely unaware Pre-action, the screen during the first two instances only shows the door, symbolizing the perspective of the longed-for woman’s coming, the theme is played first in a melancholy-charming minor mode (symbolizing the woman) and then in a questioning, unresolved seventh chord (is she coming? whether she is coming). In the third instance, where the figure listens to the cassette and dreams, the melody resounds hopefully and long in a major mode. In the second part, the Action, the figure’s posture (the same as in the third instance) is accompanied – after the first awareness-enhancing mirror scene – by the melody in a questioning, long and dramatic variation, as here the figure already faces the question (made explicit by the speaker, and enhanced by the mirror) whether the beloved will come, respectively whether the figure hears her; in the second instance in this part, too, the theme remains questioning and dramatic, until it is stopped by the Voice. After the first step of self-knowledge, this dramatic variation corresponds to the character's intensified question: Could it be that she really isn't coming and that all this hope is in vain? In the third part finally, the Re-action, the melody takes on a hopeful tone again, twice, accompanying the seated figure – after the close-ups of cassette recorder and mirror, the melody then again takes on a questioning and dramatic tone (identical to the post-mirror-scene above), and in the last sequence, after the final meeting with the boy messenger, resounds – with a final rebellion of the theme as question – in a wild, dramatic and finally sad mode. At the end, the melodies break up into chromatic scales, the string tones break into pizzicatos, and the dull, monotonous piano is entirely in the bass clef: The dream is over. The liberation from the puppet pattern of memory is also made clear musically. Here, Beckett meticulously utilizes the moods of the music, its dramatic and resolving effects. One needs to listen to the entire Geistertrio in order to understand which parts Beckett selects – and thus composes his own drama with Beethoven's music.

Further reading/sources: Knowlson 1996; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013; Romain Rolland: Ludwig van Beethoven. Berlin: Rütten & Loening, 1952; Michael Maier/Viola Scheffel 2001; Ackerley 1993, 59-64; Knowlson/Pilling 1979, 277-285; Knowlson 1986; Lawley 2001; Maier 1996.

Deutsch

Seit den 1960ern setzte Beckett die Musik in größerem Maße als eine weitere Sprache ein, in enger Verschränkung mit Sprache und Literatur – “As though they had linked their arms” (Cascando, SW III 346): So etwa in den Radiostücken Words and Music und Cascando sowie in den Fernsehstücken Nacht und Träume und Ghost Trio. Hier erscheinen Musik und Worte als im Inneren des fiktiven Autors beständig andauernde Stimmen – ist dies z.B. in How It Is oder Not I eine unaufhaltsame, ständig Text sprechende Stimme, so zeigt sich in Cascando und Ghost Trio die Musik als permanenter ‚stream of consciousness‘, der nur gelegentlich unterbrochen wird. Wie die Erinnerung (“that old past ever new, [...] with all its hidden treasures of promise for tomorrow, and of consolation for today.” Texts for Nothing 10, SW IV 328) und die erfundenen Geschichten („devising it all for company“, Company, SW IV 443) dient auch die Musik dem fiktiven Autor als Trost (“My comforts! Be friends!” Cascando, SW III 334), als Brücke auf der Flucht des sehnsüchtigen Gefangenen in die Erinnerung (an Geliebte), den Traum und die Imagination (Words and Music, Ghost Trio).

Von zentraler Bedeutung sind hierbei insbesondere zwei deutschsprachige Komponisten – Franz Schubert und Ludwig van Beethoven. Über Becketts Schubert-Leidenschaft berichten nahezu alle biographischen Zeugen: Beckett hat Schuberts Musik nicht nur in Konzerten (z.B. den Liederzyklus Winterreise mit Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in Paris; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218) und auf Schallplatten (in 1975 beschreibt Beckett sein Hörerlebnis der Winterreise als “shivering through the grim journey again”; Knowlson 1996, 626) gehört, sondern hat Schuberts Impromptus und Sonaten selbst auf dem Klavier gespielt (Knowlson 1996, 655) und dessen Lieder selbst gesungen (Lawley 2001, 263; Atik 2001); zu Becketts Annotationen in der Schubert-Biographie s. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 216-218. Insbesondere Schuberts melancholische Lieder sind für Beckett ständige Begleiter von früh an: „Beckett’s attraction to the musical form of the Lied is well known, as is his admiration of the composer Franz Schubert. In the confluence of text and music, mood and tone, Beckett found an expression of suffering and of Schwermut with which he could identify.” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 216) Entsprechend kommt Schubert in Becketts Werk immer wieder vor, vom frühen More Pricks Than Kicks (vgl. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218) über All That Fall (1956; s.o.) bis zu den letzten Werken Nacht und Träume und What Where („It is winter. Without journey.“ SW III 500; vgl. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 218). Neben der Winterreise taucht vor allem immer wieder Der Tod und das Mädchen auf – etwa in All That Fall, wo das Streichquartett gleich zweimal ominös aus einem Haus am Wegesrand erklingt (SW III 155, 184). Für Beckett ist das Quartett eng verbunden mit dem entsprechenden Text von Matthias Claudius: „Beckett’s mediation of German poetry via their setting in song (Lieder) is evident from his copy of Walter and Paula Rehberg’s Franz Schubert, sein Leben und Werk (1947 [1946]). In the index of poems set to music by Schubert, Beckett put a pen line beside Claudius’ name. Furthermore, he proceeded to write out the title and first line of various poems set to music by Schubert […]. At the top of this list, Beckett noted four poems by Claudius: ‘Abendlied’, ‘An die Nachtigall’, ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’ and ‘Wiegenlied’.” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 86; vgl. 217) Der Text von Claudius, dessen Gedichte Beckett auswendig gelernt hat (Wilm/Nixon 2013, 22; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 86; Atik 2001, 65), ist auch eine Inspiration in Krapp’s Last Tape: „When the protagonist in Krapp’s Last Tape is said to ‘look over his shoulder into the darkness backstage left’, he senses the presence of death, which in Beckett’s production notes is called ‘Hain’ (220). Beckett explained to James Knowlson that he alluded to Matthias Claudius’ poem ‘Death and the Maiden’ (set to music by Franz Schubert) and to the eighteenth-century German poet’s use of the word ‘Hain’ to refer to the death figure. In Beckett’s personal library, his copy of Matthias Claudius’ Sämmtliche Werke contains a card, inserted between pages 884 and 885, quoting a letter from Claudius to Voss (21 August 1774) that includes ‘Der Tod und das Mädchen’ […]. But the image of Hain he had in his mind is most probably the unmarked illustration next to the title page” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 10). Wie James Knowlson berichtet: „He was almost obsessed by Matthias Claudius’ poem ‘Death and the Maiden’ in which Death is seen as a comforter, welcoming the maiden into its arms.” (Knowlson 1996, 626) Der umfassendste Bezug auf Schubert in Becketts Werk ist jedoch das Fernsehstück Nacht und Träume (SW III 487-490), das die letzten sieben Takte von Schuberts Lied „Nacht und Träume“ (der Text ist ein Gedicht von Matthäus von Collin) mit der Textzeile „Holde Träume kehret wieder“ an zentraler Stelle verwendet: Hier dient die Musik – zunächst gesummt, dann gesungen – der nächtlichen Figur (dem „Dreamer“, wiederum charakterisiert als imaginierende Autor-Figur, „bowed head resting on hands“, 489) als Brücke in den Traum und die Imagination – hier der sehnsüchtige Traum von einem Trost aus dem Jenseits, der durch die Wiederholung im „close-up“ (490) des „dreamt self“ (488) an den Zuschauer übergeben wird. Die zentrale Funktion von Musik als Symbol der Flucht des in der kargen Realität Gefangenen in Erinnerung, Traum und Imagination ist hier klar erkennbar.

Von ebenso großer Bedeutung für Beckett ist die Musik von Ludwig van Beethoven: Bereits früh, in Kindheit und Studium, wie auch später im Leben hat Beckett Beethovens Variationen für Klavier selbst auf dem Klavier gespielt (Knowlson 1996, 7-8, 95, 655). Neben der Beethoven-Biographie von Romain Rolland hat Beckett auch eine weitere Beethoven-Biographie sowie den Band Beethoven im Gespräch in seiner Bibliothek gehabt (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215). Dementsprechend ist Beethoven „ present throughout Beckett’s work” (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 214). Bereits das Frühwerk ist durchsetzt mit Beethoven-Anspielungen, so auf die “unsterbliche Geliebte” in Dream of Fair to Middling Women (Disjecta 49; vgl. RR 33) oder auf Beethovens letztes Quartett (Op. 135 in F-Dur, „Der schwergefasste Entschluss“) mit der Zeile „Muss es sein? Es muss sein! Es muss sein!“ in Becketts Gedicht Malacoda („must it be it must be it must be“, SW IV 29; vgl. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215; Ackerley/Gontarski 45; Beckett hat dies noch einmal in einer frühen Version von Play ca. 1962 wieder aufgenommen, Knowlson 1996, 498); zu weiteren Beethoven-Anspielungen im Frühwerk s. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 215; Ackerley/Gontarski 45. Becketts Beethoven-inspirierte literaturtheoretische Erörterung aus dem berühmten Brief an Axel Kaun (1937) – „Steckt etwas lähmend Heiliges in der Unnatur des Wortes, was zu den Elementen der anderen Künste nicht gehört? Gibt es irgendeinen Grund, warum jene fürchterlich willkürliche Materialität der Wortfläche nicht aufgelöst werden sollte, wie z.B. die von großen schwarzen Pausen gefressene Tonfläche in der siebten Symphonie von Beethoven, so dass wir sie ganze Seiten durch nicht anders wahrnehmen können als etwa einen schwindelnden unergründliche Schlünde von Stillschweigen verknüpfenden Pfad von Lauten?“ (Disjecta 52-53) findet sich fast wortgleich in Dream of Fair and Middling Women (Disjecta 49) wieder (vgl. Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 214-216). Bislang nicht bemerkt worden ist, dass Beckett sich auch in der mittleren Schaffensphase an Beethoven orientiert, mit einem langen Gedächtnis für Romain Rollands kurze, aber eindrucksvolle Biographie: So ist der von Verdauungsbeschwerden geplagte, kurzsichtige und schwerhörige Krapp in Krapp’s Last Tape („Very near-sighted (but unspectacled). Hard of hearing.”, SW III 217) in allen diesen Details ein Spiegelbild des von Romain Rolland beschriebenen Beethoven. Und nicht nur darin: Wie Krapp („until that memorable night […] in the howling wind, never to be forgotten, when suddenly I saw the whole thing. The vision at last. […] the fire that set it alight. What I suddenly saw then was this, that the belief I had been going on all my life, namely –“, SW III 222) neigt auch Rollands Beethoven zu schwärmerischen Ausbrüchen: „Ich schreibe jetzt eine Oper! Ich habe die Hauptgestalt in mir, wo ich gehe und stehe. Nie war ich noch auf solcher Höhe! Alles Licht – alles rein und klar!“ (RR 31); Rollands Beschreibung von Beethoven – “unaufhörlich war er sterblich verliebt, unaufhörlich träumte er von unerhörtem Glück, das zerrann und bittere Leiden im Gefolge hatte. In diesem Wechsel von Liebe und stolzem Sich-dagegen-Auflehnen ist die reichste Quelle von Beethovens Inspiration zu suchen, bis dann später das Feuer seines Temperamentes nur noch unter melancholischer Resignation glimmt.“ (RR 25) – ist dementsprechend durchaus in Parallele mit Krapp zu lesen: “the fire that set it alight” (SW III 222), “with the light of the understanding and the fire” (222), und schließlich in dem entscheidenden Ausdruck “Not with the fire in me now” (226).

Die detaillierteste und präziseste Verwendung von Musik in Becketts gesamtem Oeuvre findet sich jedoch in dem Fernsehstück Ghost Trio, das auf Beethovens sogenanntem „Geistertrio“ (Opus 70 Nr. 1) aufsetzt (der Bezug des Beethoven-Trios zu Geistern entstand erst posthum über die zeitliche Assoziation mit Beethovens Planungen für eine Oper auf Basis von Macbeth – Beckett kannte diesen Bezug, vgl. Knowlson 1996, 621). Becketts akribische Arbeit an Beethovens Noten bei der Entstehung von Ghost Trio (Knowlson 1996, 621-622) spiegelt sich in der nuancierten Verwendung verschiedener Musikpassagen im Stück wider. Wie z.B. in …but the clouds… und Ohio Impromptu ist hier die Sehnsucht nach einer verlorenen/verstorbenen Geliebten zentrales Thema des Stücks. Wie in Nacht und Träume steht in Ghost Trio Musik für die Suche des in seinem Schicksal Gefangenen nach Trost in Sehnsucht, Traum, Imagination und Erinnerung; die Musik erscheint als laufende innere Stimme der Erinnerung an und des Traums von der Geliebten (die Vorstellung des tauben Beethoven, der die Musik nur innerlich hört, passt hierzu durchaus). In Ghost Trio erfährt das Beckettsche Thema Sehnsucht, Traum, Imagination und Erinnerung jedoch noch einmal eine Abwandlung/Zuspitzung: Die Kreatur im Stück ist nicht nur in einem Beckett-typischen kargen Raum, sondern auch in dieser Erinnerung, dieser Sehnsucht gefangen – die Kargheit des Raums spiegelt hier wider, dass es für die Figur außer dieser sehnsüchtigen Erinnerung nichts mehr gibt. Das Stück zeigt einen schrittweisen Prozess der Bewusstwerdung dieses Gefangenseins und der Befreiung von dieser sehnsüchtigen Erinnerung durch Selbsterkenntnis. Um dieses Drama im Stück nachvollziehen zu können, ist neben dem Beethoven-Trio ein weiterer Hintergrund des Stücks, ebenfalls aus der deutschen Kultur, hilfreich: Beckett hatte Heinrich von Kleists Essay Über das Marionettentheater (1810) 1969 von einer deutschen Schaupielerin geschenkt bekommen und verwies in der Folge mehrfach bei der Regiearbeit auf diesen Text, so auch bei der BBC-Umsetzung von Ghost Trio (Van Hulle/Nixon 2013, 97; Knowlson 1996, 584, 632-633). Kleists Schilderungen der Marionette, die durch einen Mangel an Selbstbewusstsein eine höhere Eleganz und Symmetrie in ihren Bewegungen habe, sowie vom fechtenden Bären, der durch fehlendes Selbstbewusstsein nicht auf Finten hereinfällt, machen noch deutlicher, dass es sich in Ghost Trio um das Drama einer Bewusstwerdung handelt: Die von den Fäden der Erinnerung gehaltene Marionette weicht plötzlich von ihren ewigen Wiederholungen ab und realisiert in drei Momenten der Selbsterkenntnis (Nahaufnahme des Cassettenrecorders, Nahaufnahme des Gesichts im Spiegel, Auftreten des Botenjungen), dass die erinnernd-träumende Hoffnung, in der sie gefangen ist, vergeblich ist und die ersehnte Frau niemals wiederkehren wird. Vergegenwärtigen wir uns das Stück, das wie Beethovens Trio in drei Teile geteilt ist – Pre-action, Action und Re-action: Im ersten Teil, der Pre-action, führt die kommentierende „Female Voice“ die Elemente des Stücks ein, die Teile des Raums und die Figur. In Teil 2, der Action, durchläuft die Figur dann einen Zyklus von Verhaltensweisen, den die Voice vorab jeweils futurisch durchkommentiert („He will now …“); als die Figur zur Bettstatt kommt, weicht sie jedoch zur Überraschung der Kommentatorin von den bisherigen immer gleichen, automatischen, marionettengleichen, unbewussten Verhaltensweisen ab und sieht stattdessen in den Spiegel – und auch danach geht sie statt wie angekündigt zur Tür zum Sitzplatz. (Der Topos des Gefangenseins in Wiederholungen taucht in vielen Werken Becketts auf, in Waiting for Godot und Endgame ebenso wie in Footfalls, Rockaby, Come and Go, Quad, What Where, Ping, Lessness, u.a.m. Menschen sind hier in Wiederholungen ebenso gefangen wie in Räumen.) Was hier eigentlich passiert ist, zeigt sich jedoch in der unkommentierten Wiederholung in Re-action („Repeat.“ Ist die letzte Anweisung der Stimme; SW III 435): Nachdem die Figur das erste Mal vergeblich die Tür geöffnet hat, über die er sich das Kommen der Frau ersehnt, erfolgt die erste Nahaufnahme des Kassettenrecorders, aus dem die Musik erklingt: „Cut to close-up from above of cassette on stool” (SW III 436). Hier wird (in der BBC-Aufnahme, entgegen der gedruckten Version, 433) der Kassettenrecorder erstmals als solcher ersichtlich – und symbolisiert so den ersten Schritt des Bewusstwerdens der Figur: Ihm wird klar, dass es sich nur um eine Erinnerung, eine Konserve (analog dem „recorded vagitus“ in Breath (SW III 397) und natürlich Krapp’s Bandaufnahmen in Krapp’s Last Tape, die er als „P.M.s“ (post mortems; SW III 220) bezeichnet), handelt, nicht mehr um eine Realität. Danach geht die Figur statt zur Schlafstatt (also statt des Verfallens in einen monotonen Wachen-Schlafen-Rhythmus; vgl. „no braving sleep“, Ohio Impromptu, SW III 471) zum Spiegel – “Cut to close-up of F’s face in the mirror” (SW III 437) –, wo sie, so darf man interpretieren, sich ihrer selbst und ihres Zustandes (alt, allein) bewusst wird, und beugt betrübt den Kopf (“Head bows”, 437). Beim zweiten und letzten Gang zur alles entscheidenden Tür wird die Sehnsucht nun endgültig enttäuscht – der hier wie in Waiting for Godot auftauchende Botenjunge (hier final, nicht wiederholend, wie in Godot; Beckett hat auf die Ähnlichkeit zu Godot hingewiesen, s. Knowlson 1996, 621-622) schüttelt den Kopf (“Boy shakes head faintly”, 437) und signalisiert so, dass die ersehnte Geliebte endgültig nicht kommen wird, endgültig unwiederbringlich ist. Die Figur kehrt ein letztes Mal zum alten Traum, zur Musik, zurück, die dann zu Ende läuft – danach sieht die Figur erstmals klaren Auges in die Kamera und deutet ein Lächeln an. Die Marionette ist durch Selbsterkenntnis endgültig aus dem Gefängnis ihrer Erinnerung befreit (ein analoges Ende findet sich in dem ebenfalls erinnerungszentrierten That Time).

Welche Rolle spielt hier nun die Musik? Beckett nutzt hier seine genaue Kenntnis der Beethovenschen Komposition ebenso wie sein hohes Bewusstsein des gestischen Potentials von Musik (das z.B. die Regieanweisungen in Words and Music ganz explizit machen: „Warm suggestion“, „Renews timidly“ (SW III 334), „Discreet suggestion“ (335), „More confident suggestion“, „Invites“, „Brief rude retort“ (336)). Beckett setzt dementsprechend die Beethoven-Themen sehr bewusst ein – er zerlegt Beethovens Largo (das Mittelstück des Trios) in passende Stücke und verändert die ursprüngliche Reihenfolge für seine eigene Dramaturgie. Alle Stellen, die Beckett für sein Stück verwendet, beginnen mit dem Leitthema des Largo auf der Violine. Es gibt acht Stellen, an denen die Musik angespielt wird: In der noch gänzlich unbewussten Pre-action wird bei den ersten zwei Malen nur die Tür als Perspektive des Kommens der Frau gezeigt, das Thema wird erst als melancholisch-liebliches Moll (das die Frau signalisiert Frau) und dann fragend-septimisch-unaufgelöst (kommt sie? ob sie nicht käme?) angespielt. Beim dritten Mal, wo die Figur der Kassette zuhört und träumt, erklingt die Melodie zunehmend hoffnungsvoll und lang in Dur. Im zweiten Teil, der Action, wird die Pose der Figur (dieselbe wie beim dritten Mal) nach der ersten (erkennenden) Spiegelszene nun fragend, lang und dramatisch begleitet – hier gibt es ja schon die von der Sprecherin explizierte und vom Spiegel verstärkte Frage, ob die Ersehnte kommt bzw. ob er sie hört; auch beim zweiten Musikelement in diesem Segment bleibt das Thema fragend-dramatisch (und wird von der Sprecherin gestoppt). Diese Dramatik entspricht nach dem ersten Schritt der Selbsterkenntnis der intensivierten Frage der Figur: Kann es sein, dass sie wirklich nicht kommt und ich all dieses vergeblich hoffe? In der Re-action erklingt Musik zur sitzenden Figur dann zunächst wieder zweimal hoffnungsvoll, nach den Nahaufnahmen von Kassette und Spiegel dann wieder (identisch zur obigen Nach-Spiegel-Szene) fragend-dramatisch, und in der Endsequenz, nach der finalen Begegnung mit dem Jungen, dann schließlich noch einmal, mit einem letzten Aufbäumen der Frage als Thema, wild-dramatisch-traurig – am Ende zerfallen die Melodien in chromatische Skalen, die Streichertöne zerbrechen in Pizzicati und das dumpf abschließende, gleichtönige Klavier befindet sich komplett im Bass-Schlüssel. Der Traum ist zu Ende. Die Befreiung vom Marionettenmuster der Erinnerung wird hier auch musikalisch deutlich. Beckett nutzt hier die Stimmungen der Musik, ihre dramatisierenden und resolvierenden Effekte in akribischer Weise. Man muss das ganze Geistertrio hören, um zu verstehen, welche Teile Beckett auswählt – und so sein eigenes Drama mit Beethovens Musik komponiert.

Weiterführende Literatur/Quellen: Knowlson 1996; Van Hulle/Nixon 2013; Romain Rolland: Ludwig van Beethoven. Berlin: Rütten & Loening, 1952; Michael Maier; Viola Scheffel: "‘GEISTERTRIO‘: Beethoven's Music in Samuel Beckett's ‚Ghost Trio‘". Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui 11 (2001), 267-278; C. J. Ackerley: “Beckett’s “Malacoda”: or, Dante’s Devil Plays Beethoven”. Journal of Beckett Studies 3:1 (1993), 59-64; James Knowlson; John Pilling: Frescoes of the Skull: The Later Prose and Drama of Samuel Beckett. London: Calder, 1979, 277-285; James Knowlson: “Ghost Trio / Geister Trio”. In: Enoch Brater (ed.): Beckett at 80 / Beckett in Context. Oxford: OUP 1986, 193-207; Paul Lawley: "’THE GRIM JOURNEY’: Beckett Listens to Schubert”. Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd'hui 11 (2001), 255-266; Michael Maier: „Nacht und Träume. Schubert, Beckett und das Fernsehen”. Acta Musicologica 68:2 (1996), 167- 186.